Strategic Company Goals

The 5 Questions Every Company Should Ask Itself

Five simple questions, possibly with difficult answers but a great reminder or validation of your company’s strategic goals and purpose.

1. WHAT IS OUR COMPANY’S PURPOSE ON THIS EARTH?

Keith Yamashita

Sure, it’s a bit grand, as Yamashita acknowledges. But the business environment of today and tomorrow demands a company mindset that goes beyond mundane corporate concerns. To arrive at a powerful sense of purpose, Yamashita says, companies today need “a fundamental orientation that is outward looking”–so they can understand what people out there in the world truly desire and need, and what’s standing in the way. At the same time, business leaders also must look inward, to try to clarify their own core values and larger ambitions. In trying to unearth all of this, Yamashita doesn’t just use one big question; he employs a series of them. What does the world hunger for? What are the big challenges? Who have we (as a company) historically been when we’ve been at our best? Who must we fearlessly become?

In terms of tackling the first two questions, Yamashita believes companies “must develop a culture that is excessively curious about the outside world”–and be able to identify deep needs as well as the right “hairy problem” to focus on. Rather than try to save the whole world at once, companies should zero in on the challenge that’s most compelling and appropriate. In his client Coca-Cola’s case, Yamashita says, because of the sheer volume of bottles they put out into the world every day, the need to develop local, closed-loop recycling emerged as a pressing grand challenge.

The “who we’ve been” and “who we must become” questions require a willingness to look back (because at the finest moments in a company’s history, Yamashita holds, its core values come shining through) while also looking ahead, to envision a version of the company that does not yet exist. At the intersection of these questions resides the big overriding one about purpose–the question that matters above all else: “In the end, as a human being or an institution, you have to understand why you were put on this earth,” he says, “and what actions you’re going to take to deliver on that purpose.”

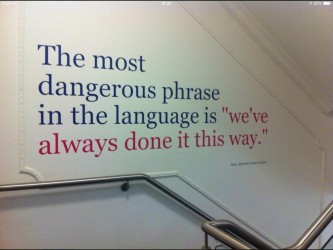

2. WHAT SHOULD WE STOP DOING?

Jack Bergstrand

There’s a natural tendency for company leaders to focus on what they should start doing immediately. But the harder question has to do with what you’re willing to eliminate. If you can’t answer that question, Bergstrand maintains, “it lessens your chances of being successful at what you want to do next–because you’ll be sucking up resources doing what’s no longer needed and taking those resources away from what should be a top priority.” Moreover, if you can’t figure out what you should stop doing, it might be an early warning sign that you don’t know what your strategy is.

And yet, Bergstrand notes, it is very difficult for most companies to decide to stop doing things–especially programs or products that were once successful. “We don’t like to kill our babies,” he says. Corporate politics can get in the way, too; individuals or groups within a company are naturally inclined to protect and defend their own projects. On top of all that, it’s just a lot more fun to focus on the new than to deal with the old. “Even asking the question about ‘what should we stop’ makes people inside a company uncomfortable,” Bergstrand says. “It often takes an outsider or a new management team to even be willing to raise the question.”

3. IF WE DIDN’T HAVE AN EXISTING BUSINESS, HOW COULD WE BEST BUILD A NEW ONE?

Clayton Christensen

Christensen, who pioneered the concept of disruptive innovation, observes that business leaders can sometimes use hypothetical “what if” questions to temporarily impose artificial constraints: What if we had to sell our $100 product for a buck; how might we go about doing that? Such questions can also be used to temporarily break free of existing constraints and biases.

Christensen’s big question is a classic example of the latter, and he loves it because it enables leaders to stop focusing on pre-existing beliefs and structures–“the stuff they’ve already invested in”–and come at the business with a fresh approach. He says the question is most useful “if, at any point in the future, you see the possibility that the core business might slow down.” But even if your company is going great guns, answering this question can point to future opportunities and help your share price to outperform the market by showing “that there’s more growth here than analysts may have thought.”

Christensen’s question could be seen as a cousin of the famous one asked by Intel’s co-founder Andrew Grove when the company was trying to decide whether to shift its focus away from making memory chips. If we were kicked out of the company, Grove asked his partner Gordon Moore, what do you think the new CEO would do? They reasoned that a new leader would feel no emotional attachment to the declining memory chip business–and would probably leave it behind. Grove and Moore did likewise, as they shifted Intel’s focus to microprocessors.

4. WHERE IS OUR PETRI DISH?

Tim Ogilvie

Ogilvie’s question is really asking, Where in the company is it safe to ask radical questions? As Ogilvie sees it, you can’t necessarily do that everywhere. “As an established business,” he says, “you’ve got all these promises you’re keeping to your current customers–you have to stay focused on that. But that may not have a future.” So the question becomes, “Where, within the company, can you explore heretical questions that could threaten the business as it is–without contaminating what you’re doing now?”

In answering that question, it’s up to company leadership to “provide permission and protocols for experimentation,” he says. That means supplying the time and resources for people to explore new questions, as well as establishing methods: “how might we” questioning sessions, ethnography, in-market experimentation. It can also mean cordoning off this area of the business, but not too much. There should be a clear line of visibility between the core business and the “Petri dish” part of the company–so that each can influence the other.

Ogilvie says another way to phrase this question is, Where is the place we can be a startup again? And surprisingly, he thinks it’s a question that even startups should ask themselves. “Startups are so desperate not to be a startup,” says Ogilvie (himself a former startup CEO). “They’re so anxious to be post-revenue and post-profit that you can almost give up what’s great about being a startup too soon. They get built for execution, and once they’re having success they’ll very quickly start thinking, ‘We’ve got to stick to our knitting.’” All of which means they’ve outgrown their original Petri dish–and might need a new one.

5. HOW CAN WE MAKE A BETTER EXPERIMENT?

Eric Ries

Shifting emphasis from Ogilvie’s where to the how of experimentation, Ries’s question is counter-intuitive for most managers, who tend to think in terms of “making products,” not “making experiments.” But as Ries points out, anytime you’re doing something new, “it’s an experiment whether you admit it or not. Because it is not a fact that it’s going to work.”

So how do companies get better at experimenting? Ries says you start with the acknowledgement that “we are operating amid all this uncertainty–and that the purpose of building a product or doing any other activity is to create an experiment to reduce that uncertainty.” This means that instead of asking “What will we do?” or “What will we build?” the emphasis should be on “What will we learn?”

“And then you work backwards to the simplest possible thing–the minimum viable product–that can get you the learning,” he says.

Just this one change–before you get to any of the more complex Lean Startup methodology–can make a world of difference, Ries insists. For one thing, it can help unlock the creativity that’s already there in your company. “Most companies are full of ideas, but they don’t know how to go about finding out if those ideas work,” Ries says. “If you want to harvest all those ideas, allow employees to experiment more–so they can find out the answers to their questions themselves.”

What better than to use

nooQ Idea Management

to debate and solve these issues.

Sign Up Today